Let’s explore the specific challenges and strategies for right-sizing Java with application fleets in cloud environments. We’ll look at GraalVM, CRaC, and Azul Platform Prime, Azul’s high-performance Java platform.

In today’s cloud-centric IT landscape, right-sizing compute resources has emerged as a critical challenge for developers, DevOps and site reliability engineers worldwide. The main driver for right-sizing is typically reducing wasted resources and lowering cloud spending. But these considerations need to be balanced with other business requirements, such as performance and operational complexity. The goal is finding the sweet spot: lean enough to be cost-effective, yet robust enough to ensure reliable service delivery.

While most cloud optimization strategies are programming language agnostic, Java applications present unique challenges for right-sizing. Moreover, a new class of Java runtimes, called high-performance Java platforms, has emerged to provide relief for some of the problems specific to Java. These next-generation platforms offer improved startup times, reduced memory footprints and more predictable performance characteristics — fundamentally changing the way we approach Java application sizing in cloud environments.

Let’s explore the specific challenges and strategies for right-sizing Java application fleets in cloud environments. We’ll examine key optimization areas, diving into Java-specific considerations for each and demonstrating how high-performance Java platforms can streamline these efforts.

The goal of right-sizing Java applications

In a perfect world, we would only provision, and pay for, the resources needed to meet traffic at any given time and spin those resources down when they are not needed. Most importantly, this elastic scaling would happen without compromising response times, service-level agreements (SLAs) or user experience.

The main areas of work in right-sizing your fleet are typically:

- Vertically right-sizing each pod to minimize idle resources.

- Horizontally right-sizing the fleet to make sure you have enough server instances to handle the load.

- Setting up a scaling policy to adjust the number of servers based on load.

The devil is in the details

With all cloud technologies, there is friction between the goals of saving money and providing maximum performance. While demand can spike immediately, it takes time to provision the server infrastructure (K8s nodes, EC2 instances, etc.) to meet that demand. These cold-start latencies force organizations into a challenging trade-off: either maintain excess capacity at higher cost to handle potential spikes or risk service degradation during demand surges. Most companies err on the side of over-provisioning, prioritizing performance and reliability over cost efficiency.

Examples of sacrificing cost for performance are:

- Leaving servers on all the time regardless of load.

- Using a low percentage of resources on each server.

With Java, the friction between cost and performance is even more pronounced. Even after infrastructure provisioning, Java applications need additional time and CPU resources to get to full speed. While Java delivers superior performance, security, and maintainability compared to interpreted languages like JavaScript, you pay a penalty at startup and occasionally even during steady state.

Java Startup and Warmup

The life cycle of a Java application starting up in an elastic environment looks like this:

- Node startup – Provisioning the virtual machine or container, including initializing the operating system of the container.

- JVM startup – Loading all the internal libraries of the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and preparing to run the application.

- Application startup – Loading all the bits of your code, including things like SpringBoot initialization, to the point that the application is ready to accept the first transaction.

- Application warmup – Optimizing the Java code to run at full speed based on the current server hardware and the application usage patterns. This process is called just-in-time (JIT) compilation.

High-performance Java platforms

A high-performance Java platform consists of two key components: an enhanced JDK and supporting infrastructure services. The enhanced JDK maintains full compatibility with Java SE specifications for long-term support (LTS) releases while delivering significant improvements over standard OpenJDK distributions in three critical areas:

- Faster application performance

- Reduced startup and warmup times

- More consistent runtime behavior

Beyond the JDK, high-performance Java platforms provide centralized services that work with client JVMs to achieve levels of performance and operational efficiency impossible with stand-alone JDK distributions.

In this article, the main technologies we cover are:

- GraalVM and especially GraalVM Native Image – GraalVM is an alternative JDK from Oracle that runs on the Truffle and Graal technologies. It has a free, open source Community Edition and a proprietary, closed source Enterprise Edition. GraalVM Native Image, a part of GraalVM, compiles Java applications ahead of time (AOT) into self-contained native executables, eliminating JVM startup overhead and reducing memory usage at the cost of some runtime performance optimizations and dynamic Java features.

- Coordinated Restore at Checkpoint (CRaC) – The CRaC OpenJDK project, led by Azul, aims to enhance startup and warmup times by enabling the JVM to capture and store its fully warmed up state at a checkpoint. Applications can then be restored from this checkpoint, bypassing typical initialization and warmup phases to achieve near-instant performance. CRaC is supported in multiple JDKs like Azul Platform Core, Azul Platform Prime and Bellsoft Liberica, as well as by AWS Lambda functions and many popular application frameworks like Quarkus and SpringBoot.

- Azul Platform Prime – Azul’s high-performance Java platform, an optimized build of OpenJDK. It includes Optimizer Hub, a set of services that can help servers collaborate to get better performance.

Vertical scaling

Vertical scaling is the process of adjusting the CPU and RAM available to a server to ensure there is enough capacity to handle traffic spikes while avoiding wasting unused capacity. While traditional virtual machines and physical servers require resource allocations in coarse increments, containers enable the allocation of computing resources with surgical precision.

One popular approach is to use a Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA) in Kubernetes. VPAs monitor your usage and then adjust the resources available to the pod and restart it to make the adjustments take effect.

So why not just use a VPA on your Java fleet and be done with it? Well, when resizing Java containers, you often need to adjust the command-line Java heap parameters as well as the pod size, which VPA can’t do. Also, since JVMs can “reserve” memory that isn’t being used, it is difficult for a VPA to correctly measure usage and adjust. In most cases, VPA does not work for Java applications, and you need to manually set resource limits for Java containers.

The problem for Java applications is the period of high JIT CPU activity at the beginning of the run while the JVM warms up your application.

Typically, you have to reserve CPU capacity for that compilation spike even though that capacity will sit idle during steady state. In other words, you’re paying forever for a spike that only lasts a few minutes at the beginning of your application’s run.

How high-performance Java platforms help

High-performance Java platforms for reducing wasted capacity due to JIT CPU spikes are:

- AOT in GraalVM Native Image

- Pros – By performing all optimization before the application is run, AOT reduces both CPU and memory needed to run the application.

- Cons – GraalVM Native Image doesn’t work on a large percentage of existing Java code, since AOT can’t cope with many Java patterns. The execution of AOT code is slower than the execution of code produced by JIT.

- CRaC

- Pros – By checkpointing an application after JIT has subsided, you can restore after the CPU spikes on a smaller machine.

- Cons – Existing applications using CRaC need to make code changes to properly restore applications. As CRaC is not yet widely adopted, few popular libraries have made these changes. You also need a clean-up state for transactions used to warm up your machine before snapshotting. Finally, you still need to reserve capacity for additional JIT activity (deoptimizations) that can happen later in the application life cycle.

- Azul Platform Prime – Optimizer Hub

- Pros – By offloading JIT to an external Cloud Native Compiler service, Azul Optimizer Hub works on any code. Since Optimizer Hub can handle deoptimization storms as well as initial warmup, you can remove all CPU reserved for JIT with confidence.

- Cons – Azul Platform Prime is a commercial solution based on OpenJDK, and there is increased complexity in provisioning and maintaining Optimizer Hub.

‘Stuff happens’

The other reason why people reserve lots of spare capacity, especially on latency-sensitive applications, is that “stuff happens.” From garbage collection pauses to deoptimization storms, to the JVM locking certain resources while it performs long-running tasks, you have to deal with all kinds of spiky behavior on your JVM. Thus, people often provision their containers with CPU utilization thresholds as low as 35% to reserve capacity for these spikes.

How High-performance Java platforms help

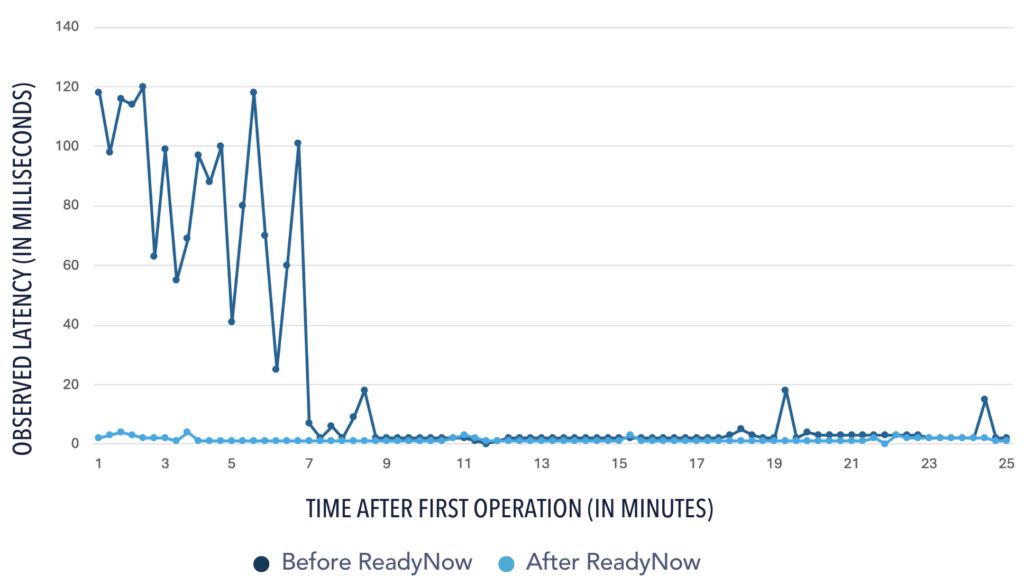

- Azul Platform Prime – The C4 pauseless garbage collector eliminates most GC pauses by allowing the application to keep taking requests while performing GC. Prime’s ReadyNow technology prevents performance disruptions caused by deoptimization storms — events where shifting application usage patterns force the JVM to discard and recompile optimized code. By maintaining and intelligently reusing optimization profiles across application restarts, ReadyNow ensures consistent performance even when workload patterns change.

- GraalVM – GraalVM Native Image optimizes all code ahead of time, meaning there are no deoptimization storms when usage patterns change. A side effect of AOT compilation is that the code runs slower than code optimized with JIT compilation.

Horizontal fleet-sizing

Horizontal fleet-sizing is the process of setting the number of servers running at any time to meet the current traffic. The number of servers needed is a function of each server’s carrying capacity — how many transactions each server can handle while still staying within SLAs.

The best way to reduce horizontal fleet-size is to get more work out of each server. Several high-performance Java platforms have advanced JIT compilers that can perform individual transactions with lower CPU than OpenJDK and can therefore complete more transactions overall without triggering CPU-based autoscaling policies.

High-performance Java platform solutions

- Azul Platform Prime – The Falcon JIT compiler produces code that runs up to 40% faster than standard OpenJDK. Azul Platform Prime also eliminates most application pauses and jitters, thus raising the carrying capacity on servers that have latency-based SLAs.

- GraalVM – While both GraalVM CE and GraalVM Native Image produce code that is slower than OpenJDK, the paid GraalVM EE has an advanced JIT compiler that produces code faster than OpenJDK.

Scaling server count to meet demand

The best way to optimize a server to save money is to just turn it off completely. The elastic nature of the cloud means you can scale servers up and down, either on a schedule or autoscaling based on load, so you only pay for what you use.

But while autoscaling sounds simple, it’s actually complicated and often requires re-architecting. Even an application written to scale up and down is subject to Java startup and warmup concerns, making it operationally difficult to ensure good performance on newly provisioned servers. A lot of developer and DevOps time is spent figuring out how to get those servers to be ready to accept traffic at speed early enough to deal with a sudden spike of traffic.

To summarize, here are the pros and cons I’ve described above for high-performance Java solutions:

- GraalVM Native Image

- Pros – Solves for both startup and warmup, typically achieving time to first transaction in milliseconds, and there is no JIT while running.

- Cons – Doesn’t work on a large percentage of existing Java code, since AOT can’t cope with many Java patterns. The execution of AOT code is slower than the execution of code produced by JIT.

- CRaC

- Pros – Solves for both startup and warmup, but allows for full code speed even when traffic patterns change.

- Cons – Existing applications using CRaC need to make code changes to properly restore applications. As CRaC is not yet widely adopted, few popular libraries have made these changes. You also need a way to clean up state for transactions used to warm up the machine before snapshotting. Finally, you still need to reserve capacity for additional JIT activity (deoptimizations) that can happen later in the application life cycle.

- Azul Platform Prime and Optimizer Hub

- Pros – By offloading JIT to an external Cloud Native Compiler service and learning the best optimization patterns from other servers, Optimizer Hub brings your application to full speed more quickly than OpenJDK. Since Optimizer Hub can handle deoptimization storms as well as initial warmup, you can remove all CPU reserved for JIT with confidence.

- Cons – Azul Platform Prime is a commercial solution based on OpenJDK, and there is increased complexity in provisioning and maintaining Optimizer Hub.

Conclusion

When your business runs on Java, you have special concerns when trying to balance cost with performance and operational flexibility. Using a high-performance Java platform can eliminate some of the trade-offs and deliver lower cloud costs at the same or better performance.

With a high-performance Java platform, you can:

- Eliminate wasted resources on each server (vertical right-sizing).

- Meet demand with the lowest number of servers (horizontal right-sizing).

- Dynamically scale the number of servers based on the current load (autoscaling).

This article originally appeared in The New Stack.