A lot has changed since Java and the JVM were created in the mid-1990s. The invention of Java solved an important problem that caused developers to spend enormous time coping with memory problems, memory leaks. Java and the JVM solved that problem, enabling Java developers to focus more on accomplishing the objective the software was intended to attain, rather than debugging memory issues. Unfortunately, Java’s solution, Garbage Collection (GC), created a new kind of problem: sudden random delays in an application’s performance. Today, such delays are intolerable.

In this article series, we’ll focus on metrics and factors related to performance within the context of latency, in particular high tail latency. In the first article we talk about the problem and impact of software latency in general, while touching upon the unique problems Java creates with respect to application latency. Our next article will focus specifically on how Java can cause very high tail latency in high performance applications.

What is Latency

Latency is the time between the initiation of a procedure and the completion of the procedure; in other words, how long it takes for something to happen.

In the realm of software, there are many types of latency. No application can possibly be truly real-time (that is, zero latency: zero time elapses between the initiation of the procedure and the delivery of the result). Still, the objective of all high-performance applications is to be as close to real-time as possible.

Types of Latency

An interesting article in InfoWorld defined 4 sources of latency:

- Network I/O

- Disk I/O

- The operating environment

- Your code

Network I/O can be a big problem especially if your application needs to traverse the Internet to gather data from external sources. The time required to even connect to the remote server can vary widely, producing very different latencies for an application. Even an internal network’s performance can vary, altering the performance of your application if it calls an internal service.

Disk I/O is an obvious problem, which is why modern applications use memory as much as possible to lower latency; but sometimes disk I/O is required, for example in the case where data is arriving from a satellite for processing within a data center. The data may arrive as a file which has to be stored on disk then read by the analysis application.

Different operating environments provide different performance: “The operating environment in which you run your real-time application—on shared hardware, in containers, in virtual machines, or in the cloud—can significantly impact latency.”

What you, as a developer, have most control over is your code. But, even here, there are differences: different languages have different latency for the same computations. For example, the performance of C/C++ differs from the performance of Python. Unlike C/C++ and Python, which provide generally static performance, Java Virtual Machine (JVM) languages are unique: second-level Just-In-Time (JIT) compilers can re-optimize the byte code based on which code paths are being used most at a given time; however, the JVM also includes Garbage Collection (GC), which in most algorithms results in application threads being paused while different aspects of GC are performed.

In addition, input data sets can affect latency, particularly in cases where the software is performing mathematical analysis of a data stream. Sometimes the input data set has an easy solution, and complex code is never entered. Other times the input data requires a much more complex path through the software, resulting in significantly higher software processing time. This can be the case, for example, in financial trading systems or scientific data analysis systems like weather forecasting or analyzing military satellite data streams. Here is where second-level JVM JIT compilers excel. Languages like C/C++ and Python cannot adapt and optimize for changing data conditions. JVMs that use adaptive compilation strategies can.

Software Latency Example

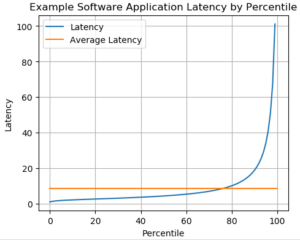

Here is a simple graphical example of what latency can look like for a typical high-performance application. We have a process being initiated repeatedly over time, with latency results that are mostly small, mostly within a narrow range; but occasionally very high latency occurs. For high-performance applications, grouping latency by percentile often produces a plot similar to this:

The Y-axis represents some arbitrary units of time that represent your application’s typical performance. The X-axis is the result of grouping all the latency results over a period of time into percentiles. The blue line is the latency for each percentile. The orange line is the average latency over the entire time span.

Looking at the average latency, you might think “Our application does pretty well, doesn’t it? Our latency is lower than its average value 76% of the time!”

Here’s the problem. If your application has acceptable latency the great majority of the time, but extreme latency some of the time, you might go out of business. Why? Because one of your competitors’ applications might almost never exhibit ultra high latency.

If your customers need your product’s result very quickly in every instance when they use it, but sometimes they are left stranded with long waits, they’ll switch to your competitor, even though the competitor’s average latency might be higher than yours. Your tail latency is much higher than your competitor’s tail latency, so it’s safer from a business point of view for your customers who need very consistent service to switch to your competitor’s product.

The Cost of High Tail Latency: Use Cases

Let’s consider a few use cases where high tail latency is totally unacceptable, even intolerable.

- Financial Trading: The markets change very quickly. If your application delivers the right data to enable the correct trade to be made quickly, that’s good. But one long wait when a trade needed to be made could wipe hours or even days (or worse) of successful trading.

- Military Satellite Data Analysis: Military commanders rely on near-real-time analysis of incoming data streams from satellites (for example applications that analyze measurements of the ionosphere) to determine whether soldiers on the ground or in the air will have viable and reliable communications and navigation systems. A sudden long delay in receiving the needed result creates uncertainty that puts soldiers’ lives in danger.

- E-Commerce: There are many sites where the same product can be purchased. If your service is normally quick, that’s fine; but if sometimes customers have to wait for a very long time after clicking a button, and they get very frustrated, they’ll leave you and find a more reliable vendor.

- Phone-Based Apps: Users of phone-based apps understand that sometimes there are issues with networks. But, if they notice that even when the network appears fine, your app is randomly highly unresponsive (due to your own application’s high tail latency), they are unlikely to keep using your app for very long.

Low latency is critical for any application to succeed in the marketplace. However, tail latency can be a much greater determinant to the possibility of success for an application than average latency. Java itself very well illustrates the problem of high tail latency, through garbage collection.

In my next post, I will describe in greater detail how traditional Java Virtual Machines uniquely contribute to high tail latency, along with how Zing solves this problem.